The Sea Runners

Tuesday, August 7, 2018 at 6:34PM

Tuesday, August 7, 2018 at 6:34PM Another ocean novel where the water itself plays a leading role.

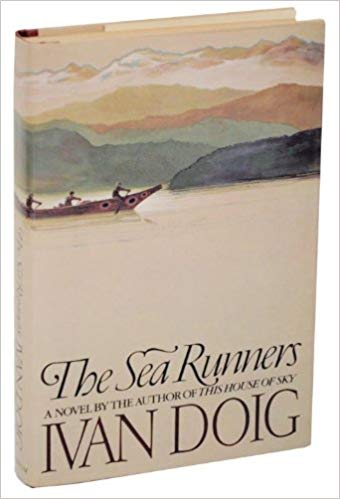

It's not giving anything away about Ivan Doig's 1982 novel The Sea Runners to say that one of the four Swedish young men trying to escape cruel indenture to the Russians in 1853 Alaska dies before they complete their 1000-mile canoe journey south to Oregon.

On the book’s first page it reads: “A high-nosed cedar canoe, simple as a sea bird, atop a tumbling white ridge of ocean. Carried nearer and nearer by the water’s determined sweep, the craft sleds across the curling crest of wave and begins to glide the surf toward the dark frame of this scene, a shore of black spruce forest…. Landing, they turn to the abrupt timber. As the trees sieve them from sight, another white wave replaces the rolling hill of water by which the four were borne to this shore where they are selecting their night’s shelter, and where one of them is to die.”

On the book’s first page it reads: “A high-nosed cedar canoe, simple as a sea bird, atop a tumbling white ridge of ocean. Carried nearer and nearer by the water’s determined sweep, the craft sleds across the curling crest of wave and begins to glide the surf toward the dark frame of this scene, a shore of black spruce forest…. Landing, they turn to the abrupt timber. As the trees sieve them from sight, another white wave replaces the rolling hill of water by which the four were borne to this shore where they are selecting their night’s shelter, and where one of them is to die.”

Another hint; the cover illustration shows only three men in the 15-foot Indian canoe they stole from the Alaska natives.

But the story is much, much more complicated and surprising than just that one death. And it is based on a true account that Doig found in an 1853 issue of the Oregon Weekly Times, a report of some Swedish men who had been found on a beach just north of the mouth of the Columbia River, “the perfect pictures of misery and despair,” who told a remarkable story of their journey by canoe down the Northwest coast from indentureship in Sitka (then called New Archangel.)

It’s almost a Mission Impossible setup, with one leader, Sven Melander getting the escape idea, and assembling an unlikely team, Wennberg, Karlsson and Braaf, who all have certain skills they bring to the crazy adventure. Braaf, for example is a small sleazy guy no one likes, but Melander tells Karlsson, “We need a thief.” That’s Braaf’s skill, and before they leave on New Year’s Night, sneaking past the drunken Russians, he steals Russian food, firearms, and most important, their maps.

A map!! In each of the ocean novels I have read this summer, I have wanted a map. How could I follow Anna as she dives in the East River around the Brooklyn Navy yard, Cora as she wanders the Essex fens, Diego as he sails northwest from Havana in pursuit of the marlin, Humphry, Maud and Wolf as they battle the sea from San Francisco to Japan to the Aleutians, Leonie and Jojo and the ghosts as the wander the bayous of southern Mississippi - without a map? But no maps in any of these books! In what waters are these protagonists sailing, diving, swimming, drowning? Where is the shore, the island, the swells, the docks? Oceans are places, have boundaries and depth charts and islands. Boats have routes, ports. I want to see them.

Finally a map, in The Sea Runners. Well it’s a map for us, the readers. We live in an era of aerial maps, satellite maps, Google maps, GPS. Not these poor Swedes. Braaf steals all the Russians’ maps he can find, but it turns out the hapless Russians, who barely ever leave Sitka and make their Swedish slaves and the native folks do all the work in the walled fort and all the seal and otter hunting, have never sailed that far south of Sitka, made no maps. Our freedom seekers get to the southern edge of their last map, the northern tip of Vancouver Island, and don’t know which way to go around the island, west or east coast. Or how far it is to Astoria, John Jacob Astor’s settlement on the Columbia River mouth that Melander had heard of. (Seattle was still 10 years away from being incorporated as a city.) The last third of their journey is done “blind,” and when some of them do finally reach Oregon Territory, they are barely alive, lost of hope and strength.

Doig began as a journalist, and later wrote extensively of his native Montana and the inland West. But he lived in Seattle where his wife taught at the University of Washington, and in this his first of many novels, he uses his journalist eye for the history, adding in the most beautiful writing of the sea I have encountered in my small summer selection of sea novels.

I was reminded of another Inland Passage tale, Jonathan Raban’s non-fiction account of his solo sailing in the 1990’s north from Seattle to Juneau, Passage to Juneau, a journey of self discovery, but also filled with lush and detailed descriptions of flora and fauna, the accounts of George Vancouver and other European explorers, and the culture and skill of the Kwakiutl and Tlingit and other natives.

Subtitled A Sea and Its Meaning, Raban’s book contrasts the Indians' understanding of their ocean with the meanings given it by European explorers. The NY Times review of Passage to Juneau summarizes the difference; “Royal Navy Captain George Vancouver's young officers thrilled in 1792 to the region's ''thundering waterfalls'' and ''beetle-browed cliffs,'' which they saw as sublime in their ''lonely and romantic vastness.'' But they thought of the sea itself only ''as a medium of access to the all-important land.''

“For the Indians it was precisely the other way around, and they viewed the hazards of the forest, with its ''wolves, cougars and grizzly bears,'' as ''more unpredictable and less easily avoided than the maelstroms and krakens of the deep.'' …Raban's comparison between the Indians' conception of the ocean as a ''place,'' a ''mobile surface full of portents, clues and meanings,'' and the white sailors' sense of it as mere ''empty space'' deserves to become standard.”

According to that distinction, ocean as place and the shore full of unavoidable hazards, or ocean as empty space, merely access to the all-important land, the Swedes actually seem more like the Indians. Of course, both water and shore present relentless danger, but on the sea they are at least on the move. Melander reads and navigates the waves well, and he is good at managing the less skilled men, both their rowing and their mood. The shore, by contrast, is full of danger to them from animals and violent Indians; our Swedes are relieved each morning to have made it through the night to get back in the canoe.

The ocean’s character here reminds me of a character in the other Pacific Ocean male adventure story I read this summer, Wolf Larsen in Jack London’s Sea Wolf. Both (ocean and Wolf) are scary and unpredictable, sometimes calm, mostly darkly destructive. But also determined and directive, a moving force able to get you thousands of miles where you want to go, faster than land. Sadly but perhaps inevitably, their successful journeys include loss of life, but some of the crew do limp into Astoria.

And like Sea Wolf, at the end of the book there’s no hint at what happens next to these escapees, far from home. The ocean can do that to you, violently take you far from home. But it can also sail you to freedom. You chose.

Copyright © 2018 Deborah Streeter