Secrets I Have

Wednesday, March 14, 2018 at 6:14PM

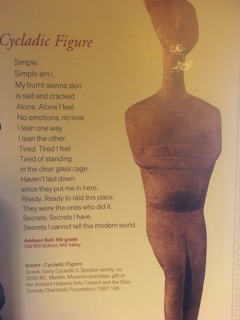

Wednesday, March 14, 2018 at 6:14PM Last week on Monday I announced on these pages that I would write weekly for a while about ocean deities. I began with the Inuit sea goddess Sedna. On Friday an ancient Aegean sea goddess came up and spoke to me, from her glass case at the Legion of Honor Art Museum in San Francisco. She said, “Write about me this week, let me speak.” She also encouraged me to read a poem that fifth grader Addison Bell had written about her as part of the “Poets in the Galleries” program at the SF Fine Arts Museums. I’ll begin with what she told Addison, that she was simple, alone, tired, ready and full of secrets.

Simple.

Simple am I.

Simple am I.

My burnt sienna skin

is sad and cracked

Alone. Alone I feel

No emotions, no love

I lean one way

I lean the other.

Tired. Tired I feel

Tired of standing

In the clear glass cage.

Haven’t laid down

Since they put me in here.

Ready. Ready to raid this place.

They were the ones who did it.

Secrets. Secrets I have

Secrets I cannot tell this modern world.

Addison Ball, 5th Grade, Mill Valley

_______

When you’re 4500 years old, I guess it’s understandable that no one remembers your name.

But still - “Cycladic Figure”? Surely they could do better than that. The names of so many of us ancient women are lost or forgotten. “Daughter of…,” “Wife of….,” “Mother of….” is the only way we are identified.

You “moderns,” as the poet Addison describes you, archeologists, and grave robbers, have found thousands of these simple, geometric, almost modern looking (you say) marble figures. Most of them are female, left in tombs on one of the Cyclades, the 200 small Aegean islands in a circle (cycle) around the holy isle of Delos.

Made of precious marble, they are small enough to be grasped by worshipper or corpse, as well as by travelers, it seems, since the figures have also been found as far away as Egypt.

These figures depict me, but I am a force mightier than any stone grave object. I am holy female, the great mother. Yes, there are a few Cycladic male figurines also, with a cute little penis between their legs. But most of us are female, and my simple triangle tells you who I am.

These figures depict me, but I am a force mightier than any stone grave object. I am holy female, the great mother. Yes, there are a few Cycladic male figurines also, with a cute little penis between their legs. But most of us are female, and my simple triangle tells you who I am.

I look small, the one Addison saw in San Francisco is only five inches tall. My people were sailors and farmers and shepherds, travelers, so they wanted a reminder of me they could hold in one hand. But even though my people lived on small islands, they were surrounded by an infinite ocean, and they knew I am as large as the waves, as deep as the sea.

I don’t think I will tell you my name. Addison heard me say, “Secret. Secrets I have, secrets I cannot tell this modern world.” You moderns want to know everything, explain, categorize. But my face is bare to show I am not just one female, not even just one god, one name. I am nameless and all names.

Later the Olympian gods of mainland Greece seized the people’s imagination and became more specialized, more individualized, more modern. We Cycladic gods and our people lost power, but we did not disappear. I live on especially in my descendants Artemis and Aphrodite. Artemis (and her brother Apollo) were born on Delos and always loved the islands and the sea, running free in nature. Aphrodite was born even earlier, on another island, Cyprus, and you have seen pictures of her, and her Roman equivalent Venus, born from the sea, rising from the waves, on a clam shell. Poor Aphrodite, she still embodies my powerful creative sexual force, but those patriarchal Greeks trivialized and fantasized about her as only seductive and self-centered. But she began, like me, as so much more, all female energy, all birth and death and sea and land and fertility and abundance.

Later the Olympian gods of mainland Greece seized the people’s imagination and became more specialized, more individualized, more modern. We Cycladic gods and our people lost power, but we did not disappear. I live on especially in my descendants Artemis and Aphrodite. Artemis (and her brother Apollo) were born on Delos and always loved the islands and the sea, running free in nature. Aphrodite was born even earlier, on another island, Cyprus, and you have seen pictures of her, and her Roman equivalent Venus, born from the sea, rising from the waves, on a clam shell. Poor Aphrodite, she still embodies my powerful creative sexual force, but those patriarchal Greeks trivialized and fantasized about her as only seductive and self-centered. But she began, like me, as so much more, all female energy, all birth and death and sea and land and fertility and abundance.

Arms crossed, always I stand that way. Well, my figures do, so my arms won’t break off. When I sailed and swam and blessed and birthed and travelled with my people beyond the grave, my strong arms and legs were always in motion, I pushed, pulled, planted, embraced, saved. Female creative energy doesn’t just stand there. Addison heard my cry that I want to move.

You moderns always want to know what we were the gods and goddesses OF. What was our specialty, our portfolio? Well, I am an island deity and an ocean deity, I comfort women in birth and all people in death, I travel with sailors on scary seas and accompany shepherds on lonely hillsides. I promise new life when winter seems endless and embody the abundance of spring. I am mother, great and powerful.

That’s all I’ll tell you. The rest is my secret.

Copyright © 2018 Deborah Streeter